What would it be like to take passage on a cemetery railroad?

Imagine it is 1854 and a new train has been built to serve your home city of London. It only has one destination. It travels 23 miles to the end of the line and back again.

Your traveling companion will have to take the train at a different time of day. You can buy a round-trip ticket, but your companion can only get a one-way ticket.

Would you want to ride it? You might. It’s a new cemetery railroad to take you, your family, and friends – and your deceased loved one – to a funeral.

All Aboard to Brookwood!

Next stop: eternity.

There was a railroad built in the 19th century specifically to service a huge new cemetery. It was called the London Necropolis Railway.

A necropolis is a large, purposefully designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. The word “necropolis” comes from the ancient Greek word νεκρόπολις nekropolis, meaning “city of the dead”.

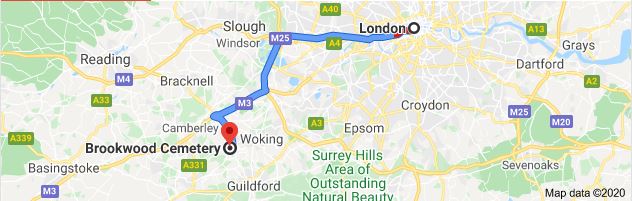

The London Necropolis Railway was built by the London Necropolis Company (LNC), to transport mourners and corpses from London to Brookwood Cemetery.

Cemetery Railroad from London to Brookwood Cemetery

Brookwood was purposely built to be far enough away from London that it would never be impacted by urban sprawl.

It was 23 miles (37 kilometers) from the city, which was too far for a horse to travel round-trip in a day.

And cars were not yet invented. They would not be introduced in England until 1892.

By placing the cemetery so far from the city with the railroad as the only means of transport, the LNC hoped to lock down a monopoly on London’s funeral business.

Why Build a Rural Cemetery?

In the mid-1800s, London was in the midst of a burial crisis. It had been a long-standing tradition to bury the dead behind the walls and under the floors of local churches – with the most wealthy and prestigious being buried closest to the altar.

But churches have four walls, right? And they don’t stretch. Alcoves were added for more burials, but space was still running out.

Crowding

When the church’s walls and floors were filled to capacity, they began to bury bodies in the churchyards.

Those who were criminals, or who were estranged from the church, were buried outside the church’s stone fences where livestock could roam over their final resting place.

Then as churchyards reached their limits, the older graves were exhumed to make room for the newly deceased.

During the early 1800s, London’s population more than doubled, from less than a million people in 1801 to almost 2.5 million in 1851. But during this same time period, the amount of land set aside for burials remained the same – approximately 300 acres (1.2 km2), divided up among about 200 small graveyards.

Sanitation

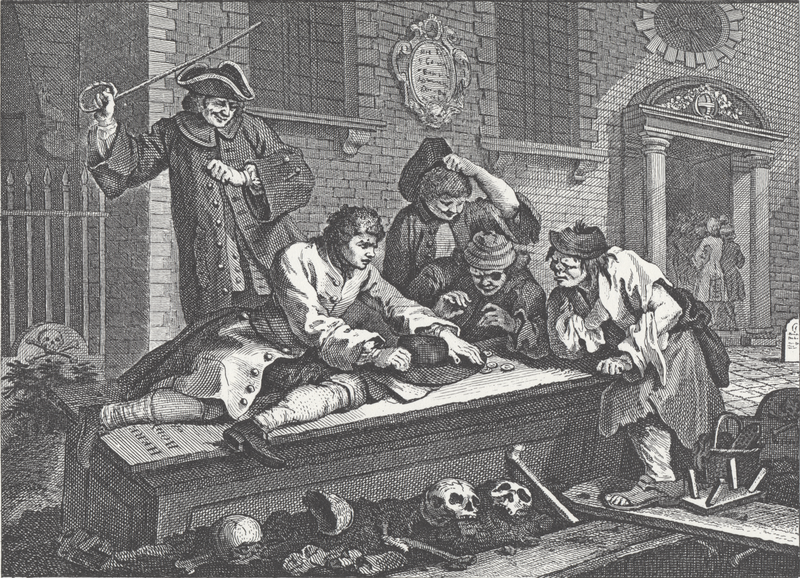

In this 1747 print by William Hogarth, a group of men are playing a game on top of a grave.

Skulls and other bones lie openly on the ground near their feet. Those are the bones from corpses that had previously occupied that grave, now unearthed to make room for a more recently deceased body.

Hogarth intended his work of art, which he titled Industry and Idleness, to show the contrast between the church-goers in the background and the gamblers in the foreground.

For our purposes, the image illustrates the casual contact between the world of the living and the dead. The people of that era had no concept of disease transmission via dead bodies.

Epidemics

In the mid-19th century, London’s Soho district was home to cowsheds, grease-boiling dens, and slaughterhouses. Animal droppings and rotting fluids ran into the streets.

The citizens of London began to complain when these fluids filtered into their cellars, forming stinking cesspools. In an attempt to solve the problem, London’s governmental leaders voted to route the filth into the Thames River.

This contaminated the city’s water supply and led to severe epidemics of cholera, measles, typhoid, and smallpox. Between 1848 and 1849, about 14,600 people died in London as a result of cholera.

So many were sick that there weren’t enough healthy people to bury the dead, so bodies were left stacked in piles by the streets until they could be interred.

Cemetery Railroad Heading Down the Wrong Track

A pair of enterprising men, Sir Richard Broun and Richard Sprye, proposed a solution to the problems besetting the city of London.

Broun and Sprye recognized that trains were a new means of transportation and rural land was cheap. So they formed a plan to take advantage of both facts.

Here was their business plan in a nutshell:

- buy 1,500 acres of inexpensive land (6.1 km2)

- assume the rate of 50,000 deaths per year would continue

- bury one family in each plot for a total of 5,830,500 graves in 1 layer

- encourage ten burials per grave for the less affluent which would yield a potential capacity for up to 28,500,000 bodies

- at that rate, it would take more than 350 years to fill a single layer

- use trains for transport since they were faster than horse-drawn carriages, making Brookwood quicker to reach than other cemeteries even though it was further away

- transport coffins and mourners on separate trains, so that there would be room to transport 50-60 bodies at once

Broun and Sprye’s plans met with resistance. Some felt that it would be too noisy and undignified to hear a train whistle or rattling wheels during funeral services.

Others were concerned that upstanding citizens would have to share a train car with those who had led immoral lives. They wanted the upper class to be separated from the lower class.

Still others felt that the families of the deceased would not want to travel on a different train from the train bearing their loved one’s coffin.

Although Broun and Sprye were eventually outed from the company, the general idea did end up being carried out.

Amazingly, the plot of land that was purchased for the cemetery was even larger than had been originally planned. It was 2,200 acres (8.9 km2), making Brookwood the largest cemetery in the world.

Brookwood Cemetery was destined to house London’s deceased for centuries to come.

Ticket, please?

Brookwood Cemetery cemetery railroad tickets were so much more than just a ride on a train!

First-class tickets allowed passengers to:

- select the gravesite of their choice anywhere in the cemetery

- erect a permanent memorial at the grave

- rest assured that their loved one’s body would not be dug up later to make room for others

- ride in a train car and wait in a train station exclusively designated for the upper-class

Second-class tickets allowed passengers to:

- have some control over the burial location

- erect a permanent memorial at the grave for an additional 10 shillings, which also meant that the LNC could not exhume the body and re-use the gravesite for someone else in the future

Third-class tickets (paid for by the Church parish) required passengers to:

- erect no permanent monument at the grave

- be buried in a separate area for paupers

- wait for train arrivals in a cellar dug beneath the train station

Funerals on the Fast Track

Some rather prominent people were buried at Brookwood. Here are a few.

Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner, Linguist

Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner (1840- 1899) showed an early propensity for languages in his childhood. His family sent him to Constantinople at age 8 to learn Arabic and Turkish. By age 10, he was fluent in both languages, as well as most European languages.

At age 15, Leitner was appointed as an interpreter for the British Commissariat (the military department responsible for the distribution of food, clothing, and supplies) in Crimea.

By age 23, Leitner was appointed to be a professor of law at King’s College in London, lecturing in Arabic, Turkish, and modern Greek. Ultimately, it was said that he was acquainted with over 50 languages and fluent in many of them.

Leitner founded many schools, literary societies, and libraries. His final ride was aboard the Brookwood Cemetery Railway.

Charles Bradlaugh (1833 – 1891), Political Activist

When Charles Bradlaugh, a member of the British Parliament, died in 1891 there was a huge funeral. More than 5,000 mourners were transported on three long trains to Brookwood Cemetery. One of the trains had 17 carriages! (That’s a LOT of train tickets!)

Bradlaugh had been an advocate of self-autonomy for India so many Indian people from London attended his funeral, including 21-year-old Mahatma Gandhi.

John Singer Sargent, Artist

John Singer Sargent (1856- 1925) was an artist from America living as an expatriate in England. He was considered to be the leading portrait painter of his generation.

Sargent was a prolific artist, creating about 2,000 watercolors and 900 oil paintings, as well as innumerable charcoal drawings and sketches.

Sargent was especially well-known for portraits that portrayed Edwardian-era luxuries, like this painting for example.

The upper-class clients that commissioned Sargent’s work would have been typical of those who also purchased 1st-class tickets on the London Necropolis Railway.

End of the Line

For nearly 90 years, a daily train had made the 23-mile journey from London to Brookwood. During its peak of prosperity, between 1894 and 1903, the train transported more than 2,000 bodies per year. But eventually, Brookwood’s cemetery railroad met its demise.

There were many factors that led to the railway’s downfall. Here are few.

Unstable Tracks

The rural plot of land with poor gravelly soil that the LNC had purchased for Brookwood Cemetery had been a real bargain. But the company owners had not considered how well the tracks would hold up over the years as heavy trains pushed the tracks into the unstable ground.

Consequently, the tracks shifted frequently and had to be continually repaired at great expense to the company.

Cemetery Railroad Marketing Woes

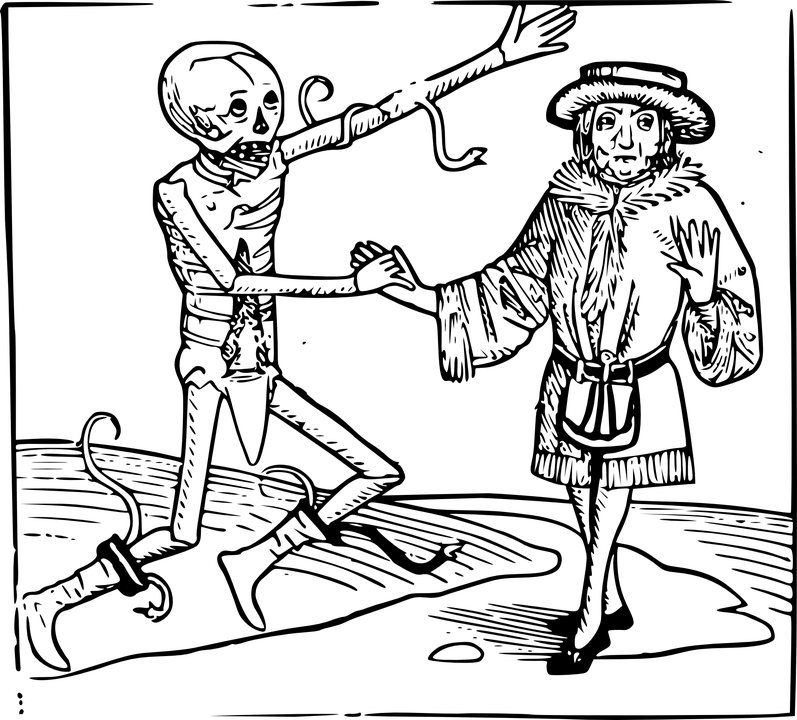

This is the London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Company logo – a skull and crossbones with an expired hourglass surrounded by a snake eating its own tail. Do you think that perhaps the company branding image was a little morbid?

Meet the Motorized Hearse

In 1909, the motorized hearse was introduced. These hearses allowed mourners to have their loved one’s coffin transported at their own convenience instead of planning around the train schedule.

It also seemed more dignified for coffins to be transported alone in a hearse, surrounded by a caravan of living family members, than to be stacked among 50-60 other coffins on the cemetery railroad.

Get Your Own Set of Wheels

By the 1940s, cars had become more readily available to the general populace, which made the railway obsolete.

Previously, with the cemetery railroad, a funeral was an all-day affair. The train left the station in London at 8:30 in the morning. Mourners typically brought along a picnic lunch – with dainty ham sandwiches, little lemon cakes, and tea – which was eaten at the train station at Brookwood Cemetery.

Then the return train took family members back to London at 3 pm. A word of warning to the weary travelers, “Don’t miss your train or you’ll be sleeping overnight at the cemetery!”

Family members appreciated that by traveling in their own cars they could now go to Brookwood at any time of day and with the people of their own choice.

Hit by Bombs

During a 1941 World War II air raid, the London cemetery railway station was hit by bombs and sorely damaged. The LNC continued to use a train station at Waterloo for the occasional train trip to Brookwood Cemetery, but the London station was never to be used again.

At the conclusion of the war, the surviving pieces of the structure were sold for office space and the cemetery railroad tracks were removed.

Interestingly, the train stations at the other end of the tracks, in the cemetery itself, remained open as refreshment kiosks. They were moderately successful for a few years but were later demolished.

A New Law for Cemetery Railroads

Following the Second World War, the four main railway companies in the United Kingdom were virtually bankrupt.

So in 1947, Parliament passed the Transport Act, turning all railways over to the government to be operated by the new British Transportation Commission.

The Transport Act was intended to bring stability to the transportation systems in the region. And it did. But the line that ran to Brookwood Cemetery was closed.

The Death of the Train Meant the Death of the Cemetery

The London Necropolis Railway was dead.

And once the railway was defunct, much of Brookwood’s land gradually reverted to wilderness.

I noted earlier that a necropolis is a large, purposefully designed cemetery with elaborate tomb monuments. But Brookwood Cemetery never did end up having very many elaborate tomb monuments.

And I mentioned that the word necropolis comes from the ancient Greek word νεκρόπολις nekropolis, meaning “city of the dead”. Although Brookwood’s 2,200-acre plot of land was big enough for a small city, parts of it were more like a ghost town.

Many of the gravesites were empty. And even today, about 80% of the existing graves are unmarked.

Though founders had planned for up to 50,000 burials per year, in reality, after 87 years of operation, there had been only 2,300 burials per year.

But even though Brookwood Cemetery was not as successful as was originally hoped, it is still the largest cemetery in the United Kingdom and one of the largest cemeteries in the world.

If you enjoyed reading this blog post you may also be interested in BillionGraves blog London’s Magnificent Seven Cemeteries. Click HERE to read it.

We appreciate your support of BillionGraves’ effort to document the cemeteries of the world!

Volunteer

If you or your group would like to help preserve history by taking photos of gravestones, go to BillionGraves.com/Volunteer . If you have questions, send us an email at Volunteer@BillionGraves.com and we’ll be happy to assist you!

Stay on track and enjoy the ride!

Happy Cemetery Hopping!

Cathy Wallace