Ostrich feather funerals might sound very odd to us in our day but in the 1800s, they were all the rage. An elegant funeral just wouldn’t have been prestigious at all without an abundance of ostrich feathers.

The fluffy plumes could be found just about everywhere at funerals – on lady’s hats, on top of the hearse, sticking up from the corners of the memorial tent, on horse’s heads, and in wreaths on the mourner’s front doors.

Funerals were used to communicate the wealth and high-class standing of the deceased and their family during the Victorian era. And one of the more obvious ways to convey prestige was to have lots of ostrich feathers at the funeral.

Abraham Lincoln’s Ostrich Feather Funeral

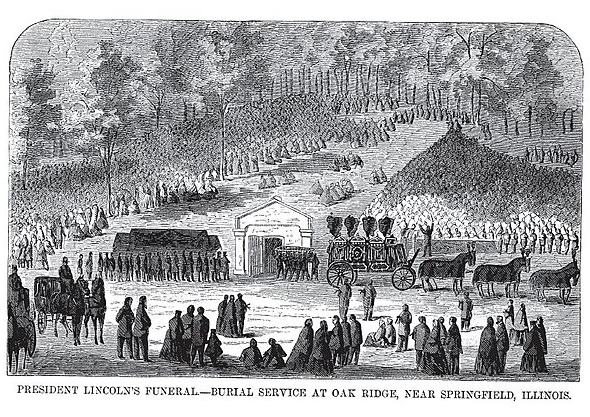

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States of America, was well-loved by the people he led and served. Great respect was shown to him at his funeral and burial service held at Springfield, Illinois in 1865.

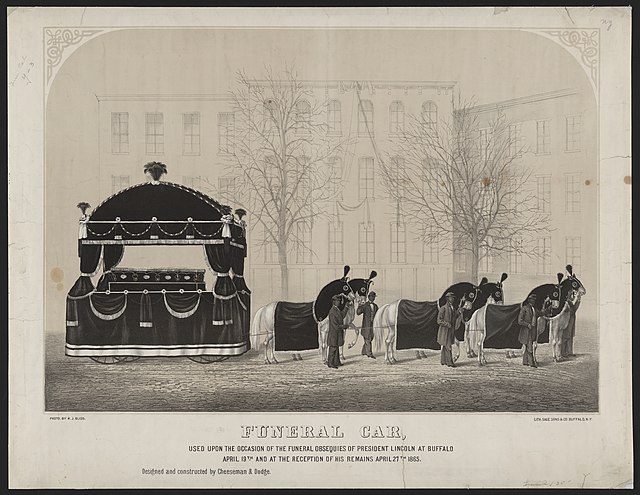

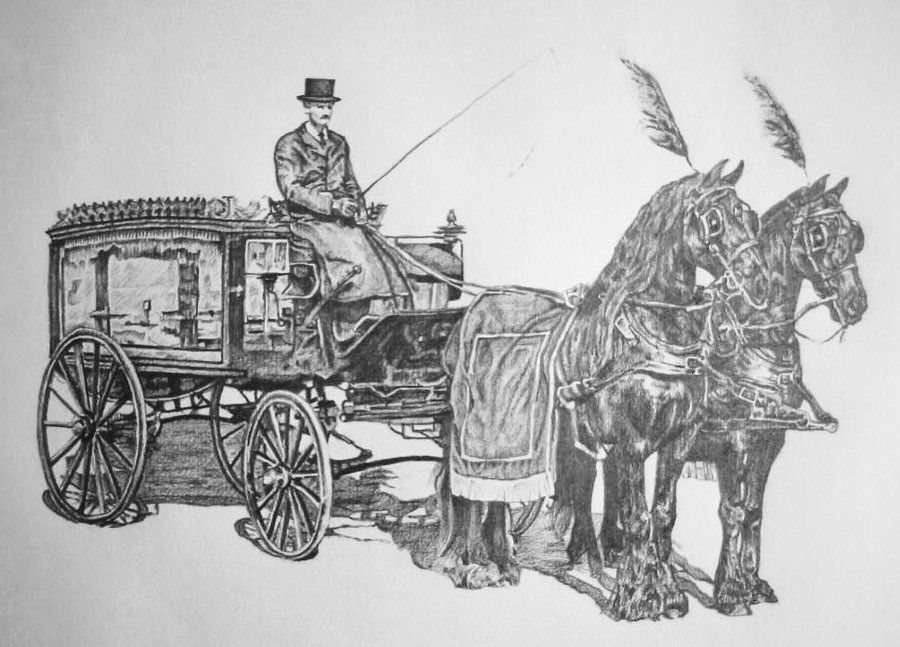

The horse-drawn hearse that bore the body of President Lincoln was a gilded 14-foot coach topped with eight plumes of black ostrich feathers.

The carriage weighed 4,600-pounds – part of which was due to the 24-carat gold-encrusted fence work and ostrich feather stands along the roof.

The image above is of a replica of the coach that carried President Lincoln’s body from Springfield’s Old State Capitol to Oak Ridge Cemetery for burial.

In addition to the huge ostrich feather plumes on the rooftop, there were ostrich feather plumes on the horses’ heads.

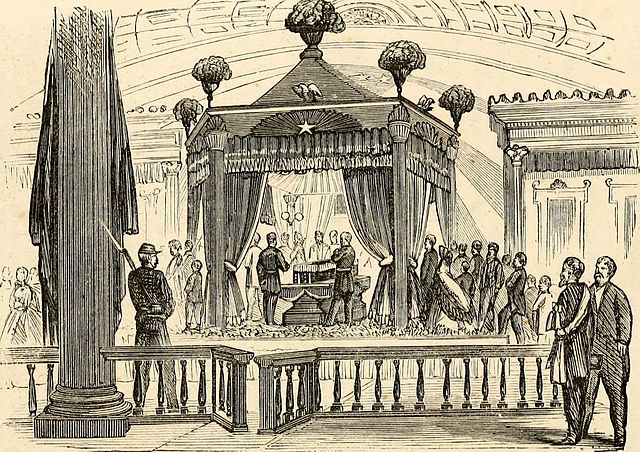

President Lincoln’s casket was transported through some of the major cities in America, like this one in Buffalo, New York.

A large plume of black ostrich feathers was on the top of this funeral coach as well as smaller plumes on each corner. Each of the six horses had a tuft of ostrich feathers sticking up between their ears.

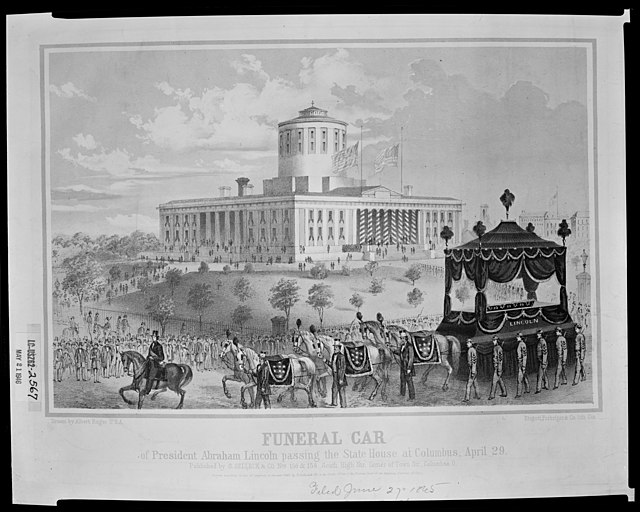

Similarly, the funeral car for President Abraham Lincoln that passed through Columbus, Ohio had an elegant coach and horses, all topped with ostrich feathers.

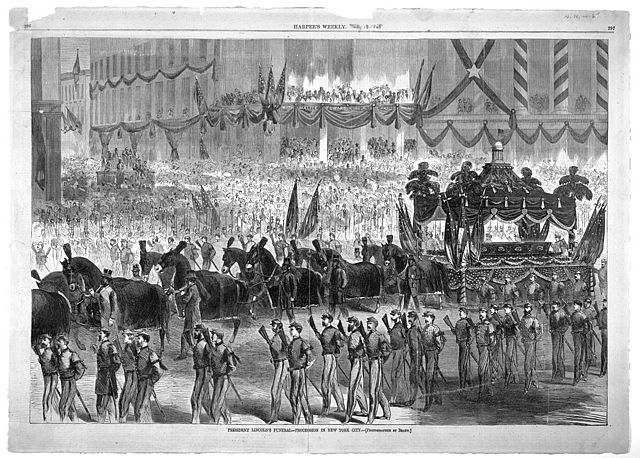

Lincoln’s New York City funeral procession had triple-layered plumes of ostrich feathers on the carriage. They almost look like little Christmas trees! The carriage was pulled by a dozen horses each with black ostrich feather plumes.

The funeral processions ended at President Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield Illinois.

Two years before his assassination, Lincoln wrote, “Springfield is my home, and there, more than elsewhere, are my life-long friends.”

The small town of 15,000 residents welcomed more than 100,000 visitors who came for the funeral services. Civil War soldiers stood by in quiet reverence near a grand canopy that had been erected for the viewing. And what noble decorations were chosen for the pinnacle? Ostrich feathers, of course!

The Duke of Wellington’s Ostrich Feather Funeral

The Duke of Wellington was the commander-in-chief of the military when Queen Victoria reigned in England.

It has been said that Wellington’s funeral was one of the greatest British events of the 19th century. It is estimated that 1.5 million people joined the procession route to the graveyard.

The funeral carriage was an eleven-ton behemoth cast from a bronze cannon that had been captured at the Battle of Waterloo. It was so unwieldy that it got stuck in the mud on the way to the cemetery and it took 61 policemen to get it out. But the ostrich feathers all over it sure looked good!

Louis-Philippe Brodeur’s Ostrich Feather Funeral

There was a long list of accomplishments and accolades for Louis-Philippe Brodeur of Canada when he passed away. He was a journalist, lawyer, politician, federal Cabinet minister, Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, and Speaker of the House of Commons of Canada.

So when his funeral procession was planned, he was honored by being conveyed to the cemetery in an 8-plume ostrich feather horse-drawn hearse.

Ostrich Feather Funeral Hats

If your ancestors were invited to an elite funeral during the Victorian era, they would have received a hand-delivered invitation at their door.

On the day of the funeral, they would have donned their finest clothes, often including ostrich feather hats and other ostrich feather accessories.

They would not have worn black unless they were a close family member of the deceased.

Lady Frances Evelyn “Daisy” Greville, Countess of Warwick, (1861 – 1938) was a social activist. She established agricultural colleges for women, founded a school for needlework, and used her ancestral homes to host events for the benefit of her workers and tenants.

She was said to have been the inspiration for the popular song “Daisy, Daisy” due to her rather unorthodox conduct. You’ve probably heard it:

Daisy, Daisy,

Give me your answer, do!

I’m half crazy,

All for the love of you!

It won’t be a stylish marriage,

I can’t afford a carriage,

But you’ll look sweet on the seat

Of a bicycle built for two!

And of course, she wore an ostrich feather hat!

Ostrich Feather Funeral Hats for Widows

Now, if your ancestor was a close relative of the deceased in the 1800s, they would have immediately donned black mourning clothes when they heard that there had been a death in the family.

And then they may not have worn any other color for years!

Mourning clothes were considered an outward expression of one’s inner grief. Going out without your black ostrich feather hat could signify that you did not love your departed family member deeply enough.

It was considered rude for anyone outside of the family to wear black mourning clothes. So if you have a photograph of your ancestors dressed in black – or with black ostrich feathers – you can be sure that they had a death in the family.

I’m not quite sure how one kept a sad countenance when wearing a hat like that!

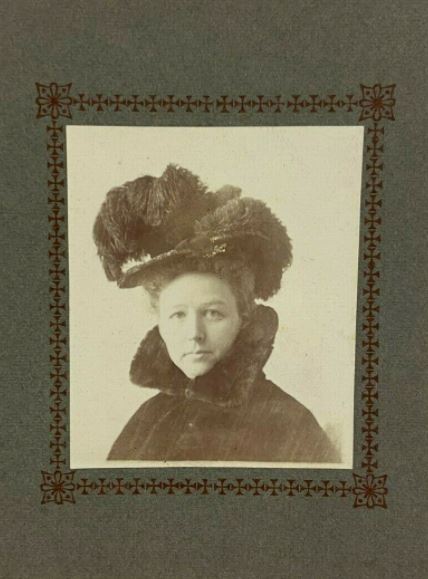

In spite of her slight smile, the black feathers on this woman’s hat, her black crepe dress, and dark fur muff, scream, “I am a widow” without her needing to say a word to anyone about it.

And that was the point of mourning clothes during the Victorian era – one wore them so that sympathy could be given without anyone having to speak taboo words such as “death” or “passed on”.

A Victorian woman was expected to remain in deep mourning for a year and a day during which she wore only simple black clothing.

This was followed by six to nine months of “second mourning” which lasted six to nine months and allowed for some use of trim and small jewelry.

Next came three to six months of “half-mourning” which allowed for more elaborate fabrics and jewelry. Colors like gray and lavender were permitted as long as there was minimal ornamentation.

An ostrich feather on the top of the mourning hat was the perfect addition.

Ostrich Feather Funeral Mourning Clothes

A proper lady of the 1800s had a black ostrich feather hat ready in her closet in case someone died.

Beaver pelts and ostrich feathers make quite a statement with this hat.

Black ostrich feathers lend a real flair to this black velvet mourning hat.

A black feather boa would be just the thing to wear to an ostrich feather funeral.

And a black ostrich feather fan with pink ostrich feather tips would be exactly right for a Victorian ostrich feather funeral. Really, dah-ling!

Ostrich Feather Funeral Horses

If your ancestors weren’t quite so “well-to-do” they may have rented a plain carriage – without ostrich feather plumes – to convey their loved one’s coffin to the cemetery.

But surely they would have at least tried to have one ostrich feather on the top of each of the horse’s heads.

Ostrich Feather Wreaths

Most wreaths in our day are hung to celebrate Christmas. But it was not always so.

One of the most common Victorian funeral traditions was to hang a wreath on the front door when a family member died.

The wreath let community members know that there had been a death in the household so that they could pass by quietly out of respect. Even children were taught to play on a different street out of ear-shot of a home with a wreath on the door.

Most funeral wreaths were made up of black ribbons or black crepe. But the nicest ones were made of black ostrich feathers.

Ostrich Feather Funerals were Big Business

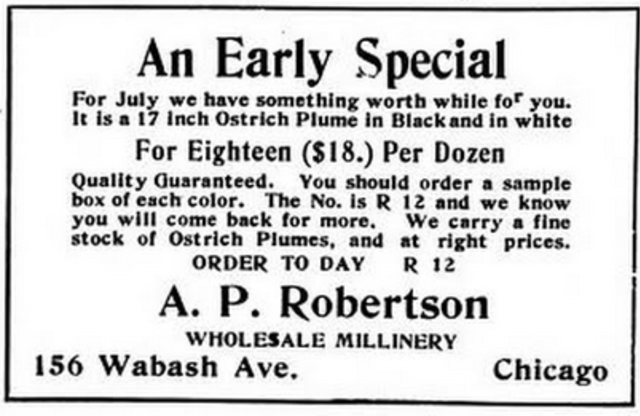

Pull out your wallet. It’s time to shop for some ostrich feathers!

Here’s a real deal. Seventeen-inch long ostrich plumes for just $18 per dozen. Nice.

But if you want some REALLY, REEEEALLY nice ostrich feathers, you better check your bank account.

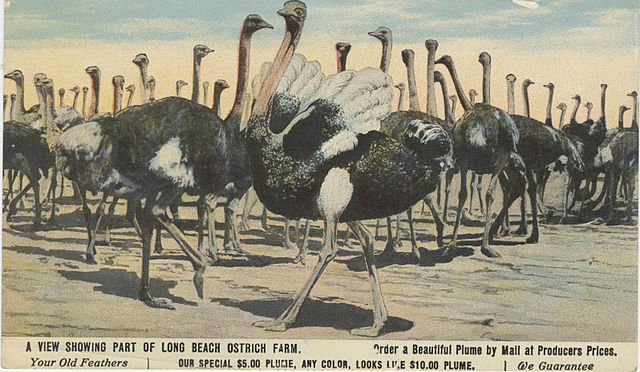

Read the fine print in this ad . . . “Our special $5.00 plume, any color, looks like a $10.00 plume.” Five bucks for one feather!

Okay, maybe you’re thinking that doesn’t sound like so awfully much. But what if you need enough ostrich feathers to top off your hat, and all your daughter’s hats, and their boas and fans. And feathers for the hearse, and for the house, and for the horse? It’s adding up, isn’t it?

Now, wait. $5 in 1850 is worth $175.00 today! Yikes! Those really were some expensive feathers!

Where Did All these Feathers Come From?

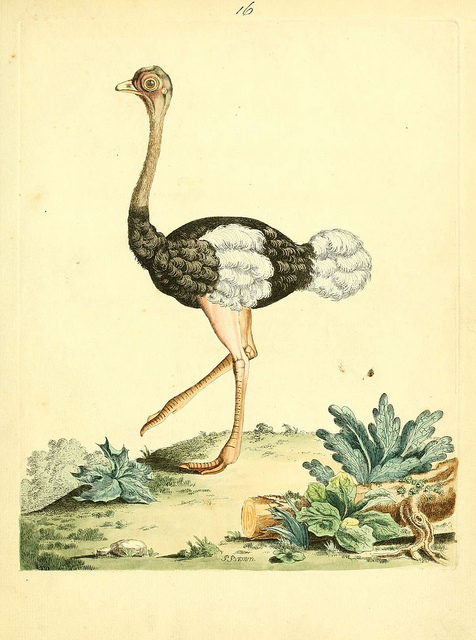

Well, from this cute little guy of course. Right out of his tail.

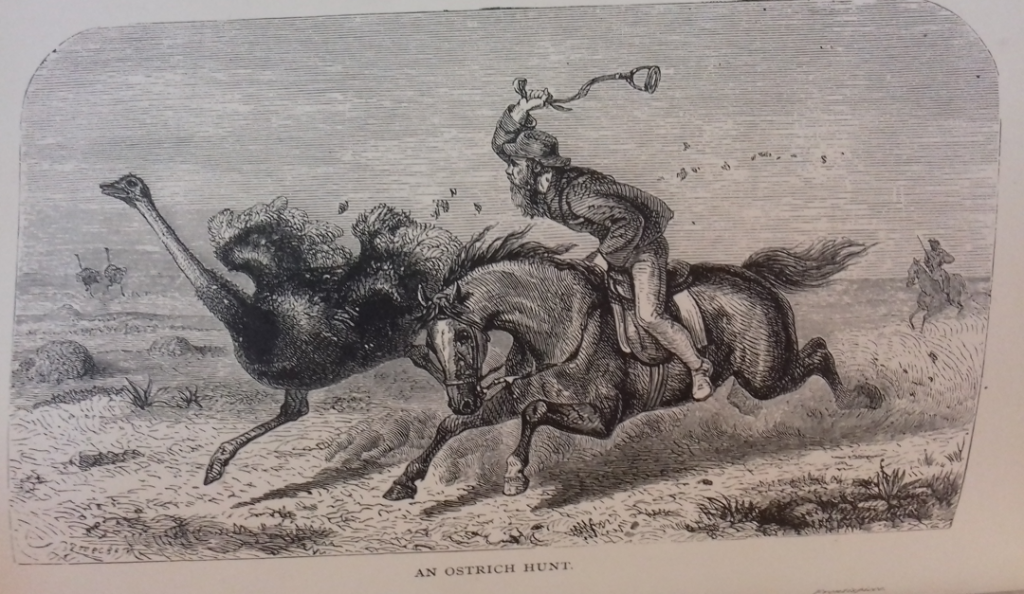

Prior to the 1860s, ostrich feathers were imported to Britain from across the Sahara desert and into South Africa where the birds were common in the wild.

Since ostriches cannot fly and they live on the open deserts, they were easy prey. Riders on horseback chased down the ostriches, killed them, and plucked their feathers.

They didn’t even have to chase the ones that got really scared and stuck their head in the sand to hide.

The feathers were then bundled up and transported in camel caravans to North Africa. Then they were loaded onto ships and sent to France or Italy and on to London where they were sold.

Feathers were Africa’s fourth-largest export – behind gold and diamonds – in the 1800s. And ostrich feathers were the most profitable because they were the most fluffy.

Ostrich Feather Farms

Of course, an ostrich that had been clubbed, shot with a bow and arrow, or poisoned was not going to produce any more feathers. But their very scarcity only increased the value of the feathers.

Eventually, some entrepreneurial-minded folks determined that there was a profit to be made in meeting the great demand for ostrich feathers. So they began to experiment with raising ostriches in captivity.

The ostrich farmers fed their birds well and built them coops.

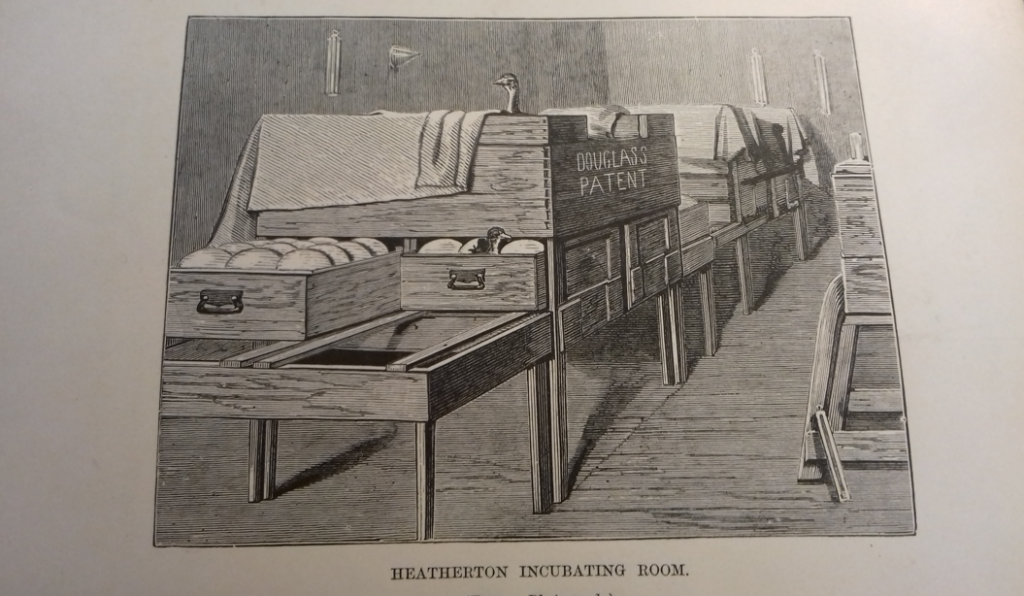

Ostrich farmers even set up incubators for the large ostrich eggs. This was helpful because the mother ostriches sometimes forgot to keep their eggs warm or even destroyed the eggs if they got spooked.

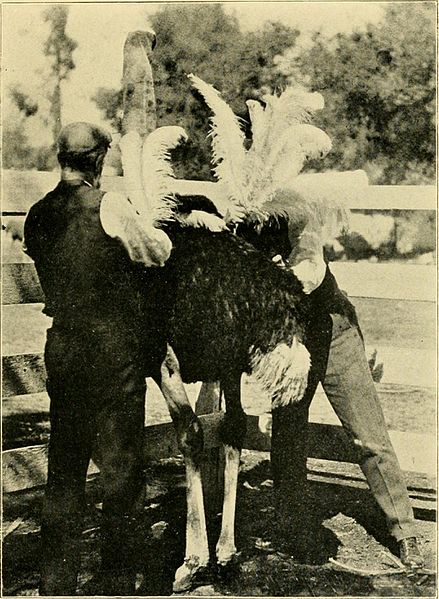

Rather than plucking feathers from dead birds, ostrich farmers clipped the ostrich feathers from the living birds so that more would grow in the next year.

A sack was put over the bird’s head while the feathers were clipped.

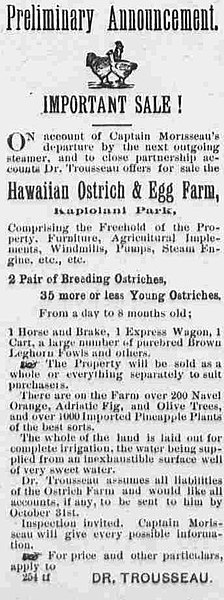

The ostrich feathers weren’t the only thing for sale – sometimes it was the entire ostrich farm.

Ostrich Feather Processing

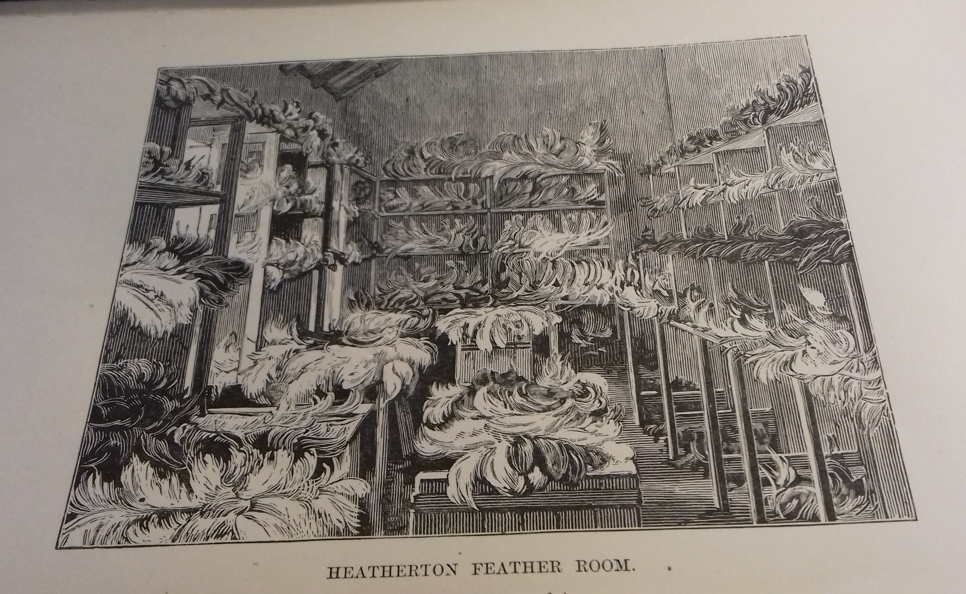

The feathers had to be sorted. Big was better than small, fluffy was better than stiff.

Just keep the feathers coming for those ostrich feather funerals!

When the Titanic sank in 1912, the most valuable cargo on board was a shipment of feathers. It was insured for $2.3 million in today’s money.

There were even ostrich feather sorting jobs.

Colored Ostrich Feathers

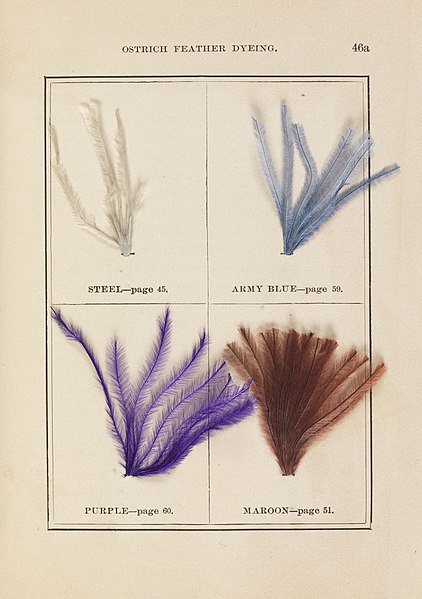

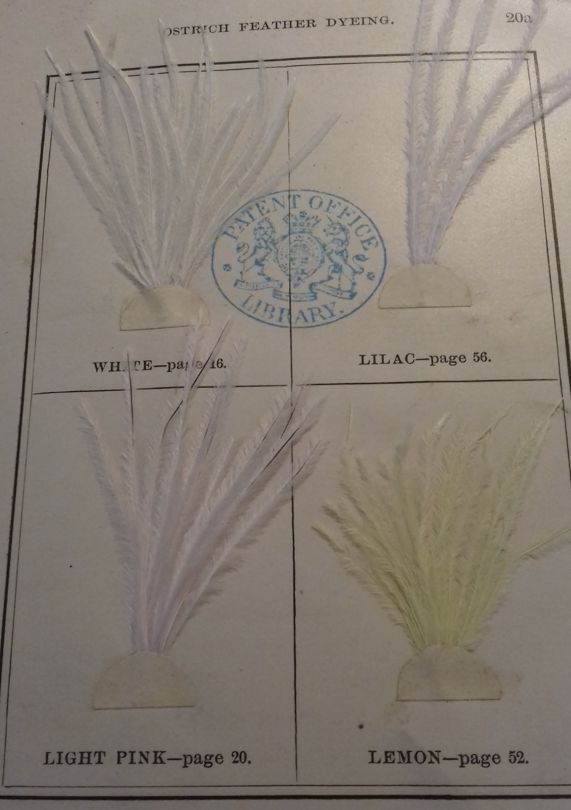

When planning an ostrich feather funeral in the 1800s, it was important to understand the rules of etiquette.

Ostrich plumes should be black if the deceased was an elderly person.

White ostrich feathers were used for children’s funerals.

A combination of white and black mourning clothes and feathers could be worn when the deceased was middle-aged or during the later stages of grief.

Ostrich feathers were even dyed different colors.

They were hand-dipped in vats and hung on lines to dry.

Your ancestors may have stopped by the local general store or millinery to check out the latest catalogs for colored ostrich feather samples like these published in 1888.

If they needed something more subtle for late-mourning stages, they could select pastel-dyed ostrich feathers.

Ostrich Feather Tourism

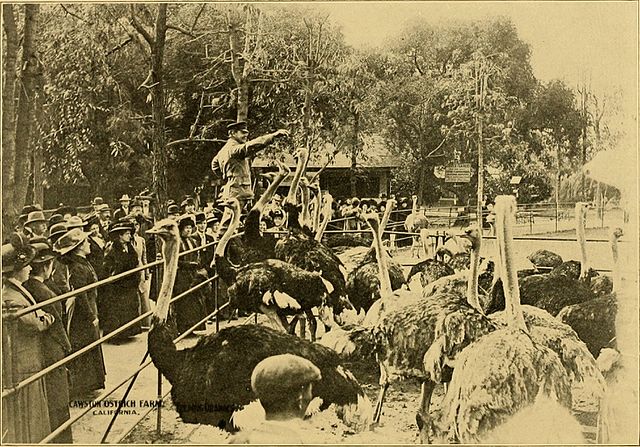

In 1885, Edwin Cawston had fifty ostriches shipped from South Africa to Galveston, Texas. From there he planned to have the ostriches sent to his farm in Pasadena, California.

Sadly, ostriches aren’t very good sailors. In rough seas, they can flip upside down in their pens causing them to be stuck on their backs with their legs flailing in the air. If they stay like that, they can die.

So every person on the ship was on 24-hour/7 day a week call, listening for the distressed cry of upside-down ostriches.

In spite of all their efforts, only 18 ostriches survived the voyage. But eventually, Cawston bred them and increased his stock from 18 to 100.

The Cawston Ostrich Farm formally opened in 1886 and quickly became a very popular tourist attraction.

Tourists could take a spin in an ostrich-drawn cart at the Cawston Ostrich Farm – while wearing the same ostrich feather hat they wore to the latest funeral of course!

Such a Fuss Over a Feather!

The decline of the ostrich feather as funeral decor came about when the feather was no longer considered to be “a rare and beautiful thing”. The ostrich farms made the feathers so plentiful that just about anyone could afford one.

Ostrich feathers ceased to be something that could only be obtained by the wealthy. And when the ostrich feathers lost the limelight, no one wanted them at all anymore.

But you know, that’s probably a good thing. Otherwise, we might all be wearing ostrich feather hats like this one to funerals.

Volunteer to Take Gravestone Photos

Now before you “make like an ostrich” and bury your head in the sand, we want to let you know that we really need YOUR help in taking photos of gravestones with the BillionGraves app!

It’s easy and done completely with your smartphone! Click HERE to get started.

You are welcome to do this at your own convenience, no permission from us is needed.

If you still have questions after you have clicked on the link to get started, you can email us at Volunteer@BillionGraves.com. We’ll be happy to help you! We will assist you in locating a cemetery that still needs to have photos taken.

Are you planning a group service project? Email us at Volunteer@BillionGraves.com for more resources.

Thanks in advance!

Happy Cemetery Hopping!

Cathy Wallace