Cemetery picnics? Those two words hardly seem to go together. But yes, cemetery picnics were a thing! And maybe, just maybe, YOUR ancestors attended them.

Today, cemetery picnics may seem morbid or even creepy, but it was a common practice in the 1800s and early 1900s in the United Kingdom and the United States. Not only were the deceased “resting in peace”, but the living were also gathering there to “rest in peace” and “eat in peace”!

Buried Beneath the Church Floor

To understand how picnics in the park became popular, let’s take a walk back through history.

From the Middle Ages to the 1700s, it had been a long-standing tradition for the dead to be buried under the floors of local churches. It was believed that the place of burial impacted the opportunity for the deceased to achieve salvation.

So the most accomplished, faithful, and prestigious community members were buried closest to the altar. Others were buried down the aisles and beneath the pews. Generation after generation, the floorboards and stones were lifted, and more coffins were added.

When the subfloors were full, burials were made within the walls. But churches only have four walls, right? And they don’t stretch. So alcoves were added for more burials. But space was still running out.

Those who were less acceptable in the eyes of God or man were buried in the churchyard. The churchyards were usually surrounded by low stone walls to keep out roaming cattle. Those who had been excommunicated, never baptized, or who had committed gross crimes were buried outside the churchyard walls.

Stinkin’ Rich

Coffins for the privileged were hollowed out from a block of sedimentary rock with a hole drilled in the bottom for drainage. The coffin lids were also hewn from rock and they rested so near the surface that the lids became the church’s stone floors. Likewise, churches with poorer parishioners had coffins with wooden lids, which doubled as the church’s wooden floors.

As you can imagine, the stench from rotting corpses within the churches was horrific. Hence, the term “stinking rich” arose from the practice of burying the affluent within places of worship. The gaseous odors were not only unpleasant, but the impact of the decaying bodies was unhealthy.

So Crowded!

Eventually, most people were buried outdoors – at first in churchyards and later in burial grounds in the town centers. By the mid-1800s, city populations were exploding. Then as graveyards reached their limits, the older graves were exhumed to make room for the newly deceased.

During the early 1800s, London’s population more than doubled, from less than a million people in 1801 to almost 2.5 million in 1851. But during this same period, the amount of land set aside for burials remained the same – approximately 300 acres (1.2 km2), divided up among about 200 small graveyards.

Some of London’s Old Gravestones

Click on the links below to see some really cool, OLD gravestones in London’s oldest cemetery, Kensal Green, on the BillionGraves’ website:

Captain George Robertson Aikman (1760 – 1844)

Sir Patrick O’Brien (1823 – 1895)

Charles Green (1887 – 1983)

William Wallen (1782 – 1853

Similarly, the Granary Burying Ground, established in 1660 in the heart of Boston, Massachusetts, was overflowing. There are 2,345 gravestones on the 2-acre lot, though it is believed that more than 8,000 people are buried there. Some were interred in mass graves, while others had headstones that have since decayed or been lost.

Famous Gravestones from Boston’s Granary Burying Ground

Click on the links below to see the gravesites of some famous colonial Americans on the BillionGraves’ website:

Samuel Adams (1722 – 1803; leader who urged colonial America to establish independence)

Abigail Adams (1735 – 1736; Samuel Adam’s 4-month-old baby sister’s winged-skull gravestone)

John Hancock (1737 – 1793; first person to sign the Declaration of Independence)

Paul Revere (1784 – 1818; messenger of the American Revolution “The British are Coming!”)

That’s Just Sick!

In the mid-19th century, London’s Soho district was home to cowsheds, grease-boiling dens, and slaughterhouses. Animal droppings and rotting fluids ran into the streets.

The citizens of London began to complain when these fluids filtered into their cellars, forming stinking cesspools. In an attempt to solve the problem, London’s governmental leaders voted to route the filth into the Thames River.

This contaminated the city’s water supply and led to severe epidemics of cholera, measles, typhoid, and smallpox. Between 1848 and 1849, about 14,600 people died in London as a result of cholera.

So many people were sick that there weren’t enough healthy people to bury the dead, so bodies were left stacked in piles next to the streets until they could be interred.

But where could they all be buried anyway? The church floors and walls were full, as were the church and city graveyards. There was a burial crisis.

Gambling on the Grave

In this 1747 print by William Hogarth, a group of men are playing a game on top of a grave.

Skulls and other bones lie openly on the ground near their feet. Those are the bones from corpses that had previously occupied that grave, now unearthed to make room for a more recently deceased body.

Hogarth intended his work of art, titled Industry and Idleness, to show the contrast between the church-goers in the background and the gamblers in the foreground. For our purposes, the image illustrates the casual contact between the world of the living and the dead. The people of that era had no concept of disease transmission via dead bodies.

Cemeteries Moving to the Countryside

To solve the problems of overcrowding and disease, city leaders in Europe and the US decided to build cemeteries outside of city limits. While rural cemeteries may have seemed like a good idea, they weren’t popular at first. Many city dwellers wanted their deceased family members to be buried close by in the city so they could visit often – even daily. They felt that traveling to rural cemeteries would be inconvenient and expensive.

So the city planners tried to make the rural cemeteries more enticing. They gave the cemeteries names like “Green-Wood”, “Abney Park”, and “Forest Lawn”. They added sweeping grassy lawns, flowering trees, walking paths, benches, and ponds with swans.

They even reinterred some celebrities from city cemeteries to the new rural cemeteries. Eventually, the idea caught on.

Paris

In June of 1804, Napoleon directed an end to all burials throughout France in places of worship and their surrounding yards. This proclamation went a long way to improving the health of city dwellers.

Napoleon’s ban created an urgent need for burial space beyond the city limits. So in December of 1804, a park-like cemetery was established outside of Paris called Cimetiere du Pere Lachaise.

Pere Lachaise Cemetery is a unique place because, unlike the crowded burial grounds of its time, it was designed to have trees, benches, and walking paths. Its park-like atmosphere was a purposeful effort to encourage city-dwellers to bury their loved ones outside of city limits.

Pere Lachaise rapidly became an inspiration for park-like cemeteries around the globe.

Famous Burials at Pere Lachaise Cemetery

Click on the links below to see the gravestones in the most visited cemetery in the world, Pere Lachaise Cemetery, on the BillionGraves’ website:

Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900; poet, playwright, and author)

Frédéric Chopin (1810 – 1849; composer and pianist)

London

In 1854, London’s Brookwood Cemetery was the largest in the world. It was 2,200 acres (8.9 km2). Even today, it is the largest cemetery in the UK.

A railway was constructed between downtown London and Brookwood to make it more convenient for visitors to get to the rural cemetery. (Learn more about the cemetery railroad by clicking HERE.)

“The Magnificent Seven” is the nickname for seven huge cemeteries that surround the heart of London. Each is a unique masterpiece of park-like greenspace. (Learn more about “The Magnificent Seven” by clicking HERE.)

USA

The rural cemetery movement in the United States began on the East Coast during the early 1900s.

Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts (established in 1831), Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (established in 1836), and Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York (established in1838) are considered the nation’s first three rural cemeteries.

Many other American cities followed their example in establishing their own rural cemeteries.

“A Stroll in the Park” was “A Stroll in the Cemetery”

Since many municipalities still lacked proper recreational areas, cemeteries were the closest things, then, to modern-day public parks. People began to use them as places to take a Sunday walk or to hold family gatherings.

Cemetery pathways were crowded with horse-drawn carriages and people in conversation.

Cemetery visitors dressed in their finest clothes. They weren’t wearing black mourning clothes though. Rather, they dressed as if they were headed to a church social or county fair.

In Dayton, Ohio, Victorian-era women paraded with parasols as they promenaded the walkways at Woodland Cemetery.

At Arlington Cemetery in Washington D.C., cemetery visitors tended flowers and chatted on benches.

“A Picnic in the Park” was “A Picnic in the Cemetery”

It wasn’t much of a stretch for a “stroll in the cemetery” to become a “picnic in the cemetery”.

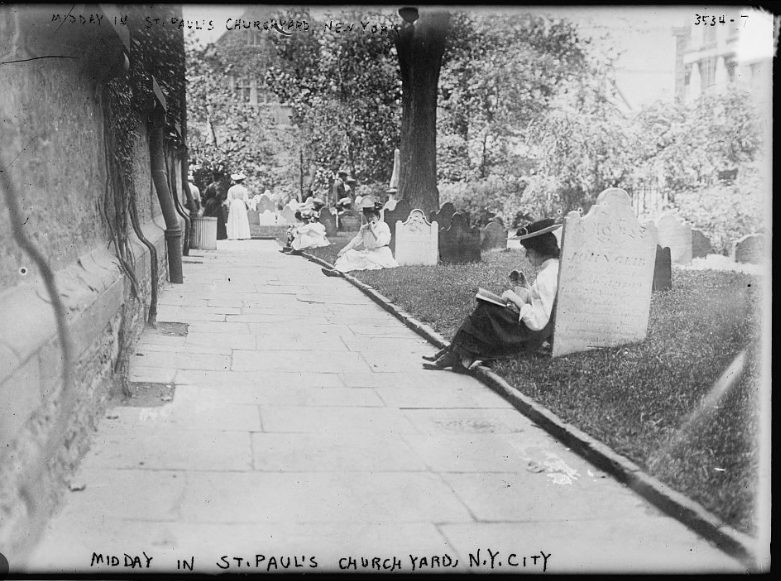

Families arrived at the cemetery gates in droves. New Yorkers strolled through Saint Paul’s Churchyard in Lower Manhattan, bearing baskets filled with fruits, ginger snaps, and beef sandwiches.

They gathered at family plots and sat on the gravestones or the ground to eat.

Picnic Ads in the Newspaper

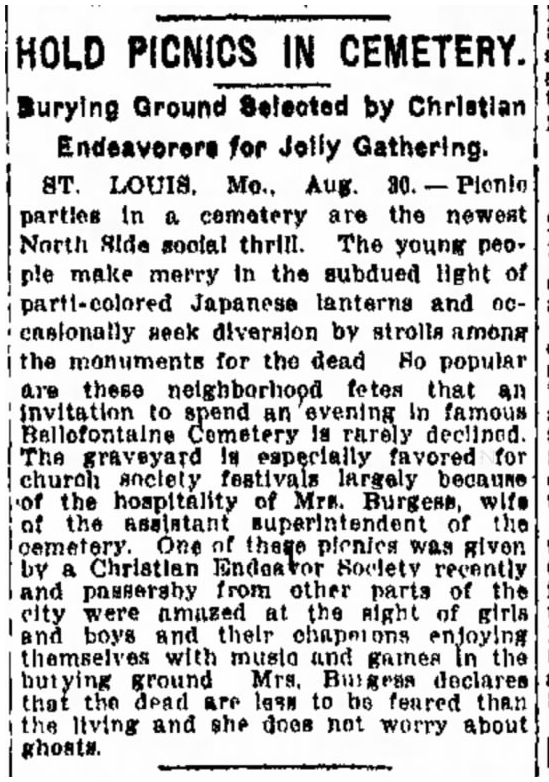

Cemetery picnics became so popular that invitations were sent out and the events were advertised in local newspapers.

Notice that they were “enjoying themselves with music and games”. Check out that final sentence, “Mrs. Burgess declares that the dead are less to be feared than the living and she does not worry about ghosts”!

Some graveyard picnics included a time to clean up the cemetery.

Even Yogi Bear Never had Picnics this Good

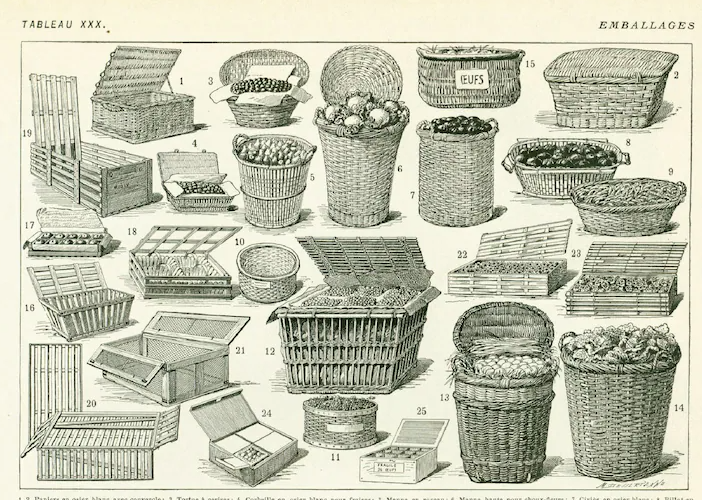

This 1922 advertisement shows the type of wicker baskets that were available for cemetery picnics.

The family’s best china dishes and silver serving pieces were laid out on handmade quilts.

What did they eat?

When the cemetery picnic baskets were opened, these are some of the foods our ancestors’ would have packed inside:

- Dainty ham sandwiches

- Cold roast beef, lamb, or duck

- Boiled eggs

- Apples

- Strawberries

- Cheese

- Watercress, lettuce, and celery

- Chicken salad or salmon salad

- Chestnuts or walnuts with cream cheese

- Sliced fresh ginger

- Cucumber with mint

- Homemade bread with fresh butter

Dessert

- Lemon pound cake

- Butter cookies

- Jam tarts

- Fruit cake

- Gingerbread

- Cheesecake

- Donuts

Beverages

Safe drinking water was difficult to come by so these were the common beverages served at a cemetery picnic:

- Lemonade

- Ginger-beer

- Soda water

- Cider

Sometimes they even set up folding tables and chairs at the family plots and served food on their fine china.

Post Cemetery Picnic Activities

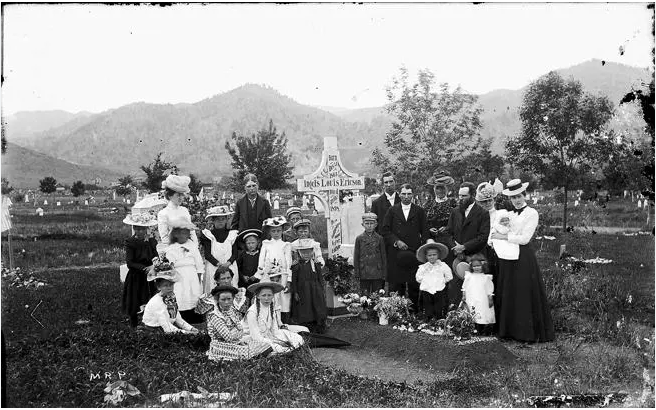

Once the cemetery picnic was over, families lingered, sometimes spending the entire day at the cemetery. They sometimes gathered for a photo at the family plot.

Others relaxed against a family headstone to read or do some needlework. Mothers who had lost babies or children liked to spend time in the cemetery near their gravestones.

End of an Era for Cemetery Picnics

Cemetery picnics began to wane in popularity by the 1920s. Medical advancements made deaths less likely so fewer families visited the cemetery for that reason. Public parks were becoming more common so recreation shifted from cemeteries to parks. (Interestingly, parks were often right next to cemeteries. You may notice that even today.)

Nowadays, there are very few cemeteries that allow picnics. Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York, for example, has an explicit no-picnicking rule.

But the fad isn’t entirely gone. Mexican families have cultural traditions of eating meals with departed loved ones, especially on the holiday called The Day of the Dead.

And some cemeteries hold occasional public events in remembrance of our ancestors’ cemetery picnics.

If you would like to hold a cemetery picnic, call the cemetery manager for permission, if appropriate. Then fill a picnic basket with food and head over to your local cemetery to recreate an old-time tradition. Take your phone with you so you can use the BillionGraves app to document the graves. Invite your family and friends – you never know who might be dying to come!

Take Photos of Gravestones

Whether you picnic at the cemetery or not, we hope you will take some pictures of headstones. We need volunteers to take gravestone photos.

When you take photos in your own local cemeteries and I take them in mine, we will all help each other to find our ancestor’s final resting places. Click HERE to get started. You are welcome to do this at your own convenience, no permission from us is needed. If you still have questions after you have clicked on the link to get started, you can email us at: Volunteer@BillionGraves.com.

Happy Cemetery Hopping!

Cathy Wallace