Discarded gravestones on the beach?! You might expect to find seashells, sea glass, driftwood, and such on a beach . . . but gravestones!?

Low tides, strong winds, and shifting sands reveal a tragic event in San Francisco’s past – gravestones that were repurposed decades ago to reinforce seawalls, build roads, and improve parks.

If you have ever wondered why BillionGraves encourages volunteers to take photos of gravestones, THIS is a great example! Taking photos of gravestones with the BillionGraves app preserves history and helps future generations to find their ancestors.

We need your help – wherever you live – to document your local cemeteries!

The History Behind the Discarded Gravestones

At first glance, San Francisco, California is strangely devoid of cemeteries. It has been illegal to bury the deceased in the city for more than 120 years.

But it wasn’t always so. In the 1800s, there were at least 30 cemeteries in San Francisco. There were Catholic, Jewish, Protestant, non-denominational, fraternal club, Native American, Chinese, and pauper cemeteries.

The “big four” cemeteries were Laurel Hill to the north, Odd Fellows’ to the west, Masonic to the south, and Calvary to the east.

All four were built between 1854 and 1865. They were laid out on rolling green lawns with winding roads and beautiful paths. Families flocked to the large park-like cemeteries to visit the graves of their ancestors and loved ones, often bringing along a picnic.

Burials Banned with City Limits

For a while, cemeteries were valued as public spaces and family remembrances, but in the meantime, nearby neighborhoods were expanding and the land was becoming more valuable.

Those who wanted to build a home by the bay began to wish that those who were “resting in peace” would rest someplace else.

By the end of the century, some of the city’s cemeteries were still in use, others had been abandoned – but ALL of them were full!

In 1900, the citizens of San Francisco voted to ban burials within city limits.

The ordinance to stop burying the dead meant that cemeteries lost money from the sales of new plots. This resulted in the cemeteries falling into disrepair.

Without the funds to fully staff and protect the cemeteries, intruders entered. Grave markers were vandalized and coffins were looted.

Voting the Dead Out of the City

In 1902, some of San Francisco’s property owners started a campaign to have cemeteries moved to less-desirable locations. They hoped that this would boost their property values.

Over the next two decades, there were campaigns and bureaucracy surrounding the cemetery debate. Voters were asked to approve cemetery relocations three times. And each time the citizens voted no.

But in the end, the deceased were not on the winning side. Eventually, the city’s Board of Supervisors declared that cemeteries were a “menace, a nuisance, and a detriment to the health and welfare of the city”.

The bottom line was that the deceased were resting on prime real estate, and like many of the living, they could no longer afford to reside there.

Between 1920 and 1941, those who were buried at the “The Big Four” cemeteries began to be exhumed and moved to Colma, a quiet town of roughly two square miles just south of San Francisco.

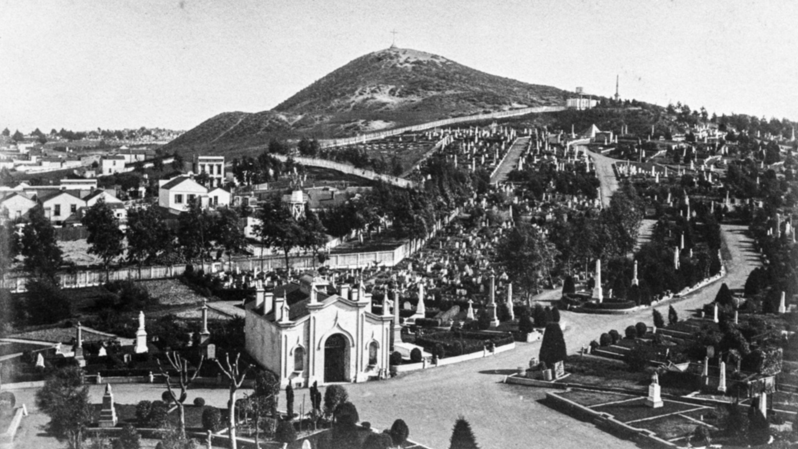

For example, this is the Odd Fellows Cemetery of San Francisco in the late 1800s – one of the “Big Four”. More than 26,000 bodies were moved from Odd Fellows Cemetery to Colma Cemetery.

Families of the deceased were contacted. They were told that the remains and the tombstones could be removed privately and reburied at the families’ discretion.

For a fee of $10, the city even would transport the coffins and gravestones the 15 miles to Colma for them. Some families paid the fee and even accompanied the deceased in a solemn procession to their new resting place.

But keep in mind that this was during the Great Depression. Many families could not spare $10.

The sad result was that many unclaimed corpses were buried in a mass grave at Colma.

More than 150,000 bodies were moved from San Francisco to Colma as farmland became graveyards.

Today, the entire city of Colma is covered mostly in graves. Some are marked graves but many are not.

Some of the San Francisco cemeteries kept records about the relocations but it was an overwhelming task. There were a LOT of gravestones! Laurel Hill Cemetery alone had covered 54 acres.

With all the cemetery chaos, San Francisco became a genealogist’s nightmare.

Unclaimed tombstones – with their precious engraved names and dates – became the property of the city.

The city then decided to use the gravestones in public spaces.

From Cemetery to Playground

Like it or not, the Department of Public Works started using the discarded gravestones in city infrastructure projects.

In 1933, workers fanned out across the now-defunct Odd Fellows Cemetery to convert it into Rossi playground.

The columbarium on the right is the only thing that remains standing from the former Odd Fellows Cemetery in San Francisco. All of the gravestones are gone.

Where did they go?

Some of the discarded gravestones from San Francisco’s cemeteries were crushed and used to build drain gutters at Buena Vista Park. Others were used to strengthen the seawalls at the St. Francis Yacht Club.

Swimmers and surfers occasionally encounter marble and granite gravestones at low tide along Ocean Beach. Names and dates peek out at the water’s edge where the discarded gravestones were used to break up the waves before they hit the shoreline.

Here are some places where you can still find glimpses of what is left of the grave markers in the San Francisco area:

Discarded Gravestones at Ocean Beach

As the remains of 35,000 bodies at Laurel Hill Cemetery were exhumed, the gravestones that were meant to be their legacy were broken into more manageable pieces and transported to Ocean Beach.

Some of the largest slabs were stacked to form diagonal walls along Ocean Beach to prevent shoreline erosion.

Even in more recent years, swimmers, surfers, and beach walkers are startled to come across discarded gravestones during low tides.

Discarded Gravestones Under The Great Highway

In 1929, a 3.5 mile (5.6 km) long four-lane road was built next to the Pacific Ocean alongside Ocean Beach on the west side of San Francisco. It was called The Great Highway.

During construction, a foundation was needed for the Great Highway. Guess what was used? Headstones.

Years later, as the railroad went by the wayside and the automobile gained greater popularity, efforts were made to improve and widen the Great Highway as well as protect it from erosion. What was used this time? More headstones, of course.

Discarded Gravestones in Buena Vista Park Rain Gutters

Established in 1867, Buena Vista is the oldest park in San Francisco.

In 1935, during the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to improve and beautify public spaces.

The program put about 8.5 million Americans to work building schools, hospitals, roads, and other public works.

Some of those WPA workers constructed ground-level rain gutters at Buena Vista Park. And what did they use? Gravestones.

Most of the discarded gravestones that were used to line Ocean Beach were left intact. But those that were carted off to Buena Vista Park were broken into fragments and used to line the rain gutters that ran along the roads and walking paths.

Gravestones were generally placed with their epitaphs facing downward but some of the names and dates are visible in the rain gutters, reminding passersby of their original purpose.

Joggers and dog-walkers are often startled to come across word fragments such as “Died”, “In Memory Of . . . ”, and “Gone but Not Forgotten” underfoot. How ironic.

Discarded Gravestones in Aquatic Park’s Sea Wall

Aquatic Park’s sea wall, designed to keep the waters calm was another project where unclaimed tombstones were repurposed.

Beach-goers can spot the rectangular gravestones mingled with the natural rocks and sand at Aquatic Park at low tide.

Discarded Gravestones at Marina District’s Yacht Harbor

Who wouldn’t fall in love with this lovely architecture? At the surface, Marina District is the site for weddings, a children’s educational center, a science museum, restaurants, and more.

But those who look deeper may find remnants of marble and granite gravestones here and there.

When discarded gravestones were shipped to the Marina District in November of 1934, construction crews worked to turn them into uniform white slabs resembling bricks. The bricks were then used to create a sea wall to protect the yacht harbor from ocean erosion.

Discarded Gravestones in The Wave Organ

Behind St. Francis Yacht Club, at the end of a jetty, there is a strange structure built to amplify the sounds of the waves.

The Wave Organ was designed by artist Peter Richards in 1986 and sponsored by the Exploratorium Museum.

The organ is made up of 25 PVC “organ pipes”, bricks, cement tubes, and – you guessed it – gravestones, cemetery statues, and mausoleums.

Roman numerals, names, and ornamentation are still visible in several parts of The Wave Organ.

Those who visit San Francisco’s Wave Organ at high tide can hear a tune reminiscent of blowing across a bottle top. But those who visit at low tide may find that it sounds more like a gurgling toilet!

The fact that there were still enough discarded gravestones available in the 1980s to construct The Wave Organ shows just how many cemetery monuments were left behind in the 1930s.

Discarded Gravestones Turning Up Everywhere!

Over the years, random discarded gravestones have been discovered in a variety of unexpected places around San Francisco.

- 1977: children from Miraloma Park called the police after they found a collection of headstones while playing on Mount Davidson

- 1998: a construction worker at Turk Street and Arguello Boulevard hit the gravestone of Pierre Giraud, a saloon owner who had died in 1878

- 2017: electricians working on a home in Laurel Heights found a 155-year-old headstone etched with the names of an entire family, including their baby boy

Today, there are only two cemeteries left inside city limits: the San Francisco National Cemetery at The Presidio and the small Mission Dolores Cemetery.

In spite of the lack of cemeteries in San Francisco, the memories of the evicted dead are hard to erase. Their memorials, after all, make up the very fabric of the city.

Take Photos of Gravestones! Wait, Why Does it Matter?

Once a gravestone is gone, a legacy has been lost. Sometimes gravestones are an individual’s only record left on earth.

As the tides ebb and flow along San Francisco’s beaches, tombstones appear and disappear. People marvel for a moment and then forget.

Damaged gravestones mean lost history. In many cases, the damaged gravestones contain not only personal family history but also community and cultural information.

But if damaged gravestones are photographed with the BillionGraves app, some of that history can still be preserved.

Better yet, taking photos with the BillionGraves app before gravestones are damaged will build a hedge against future loss. YOU can do this at your own local cemetery! Then both you and your loved ones can truly rest in peace!

How Can You Help?

We need your help with taking gravestone photos to help preserve history! When photos are taken with the BillionGraves mobile app, each picture is automatically tagged with GPS coordinates.

This allows families to easily find their ancestor’s final resting place at the cemetery so they can grow their family tree. It also allows future volunteers to see exactly what has already been photographed and what still needs to be done.

If you would like to volunteer to take gravestone photos with your smartphone click HERE to get started. You are welcome to take photos of gravestones at your own convenience, no permission from us is needed.

If you still have questions after you have checked out the resources above, you can email us at Volunteer@BillionGraves.com.

Would you like to lead a group in documenting a cemetery? Email us at Volunteer@billiongraves.com and we’ll be happy to send you some great tips!

Happy Cemetery Hopping!

Cathy Wallace